A Few Things I Learned From the World's Oldest Novel

Novelists have been equal parts exuberant and anxious for at least 2000 years.

I’m not usually a person to set reading goals, but this summer I did commit myself to one: I wanted to read the world’s oldest known novel, Chaereas and Callirhoe.

“Why have I never heard of this book?” you may wonder. If you google “world’s oldest novel” or ask most literature specialists you’ll hear the names of the earliest well-known novels, like The Tale of Genji (11th century) or Don Quijote (17th century); if you plunge into the weeds with books like Steven Moore’s The Novel: An Alternative History you’ll give up on ever getting a straight answer. But if you use the basic description of a novel as “a fictional narrative in prose longer than about 40,000 words,” Chaereas and Callirhoe, likely written in the first or second century CE, is the most obvious contender. There are novel-like texts written before 1000 CE in other languages, but Chaereas and Callirhoe is the earliest one (or one of the very earliest) any modern reader would recognize as a novel.

A little background: Chaereas and Callirhoe was written in Greek by Chariton, who, like virtually every novelist after him, had an unpleasant day job: he identifies himself as the assistant to a rhetor (that is, a lawyer) named Athenagoras who lived in Aphrodisias, a Greek city in what is now Turkey. Nothing else about him is known. He lived at the height of the Roman empire, probably (according to scholars’ best guesses) in the first or second century CE, which puts him at least 500 years after the classic era of ancient Greek literature—Euripides, Aeschylus, Sophocles, Sappho, et al. In order to give Chaereas and Callirhoe the romantic and heroic tone of an earlier age of Greek history, Chariton set the novel in Syracuse (a major Greek city in what is now Sicily) in the fourth century BCE, during the reign of Alexander the Great.

This is part of what makes Chaereas and Callirhoe, to my mind, delightfully modern—not just that it’s a historical novel, like so many of the major novels of our own time, but that it’s an anxious and self-conscious historical novel, striving to be authentic to an earlier era and not quite getting there. It’s packed with quotations and allusions to Homer and the great Greek playwrights and lyricists; Chariton is always looking over his shoulder and saying things like: “She appeared dressed in black, with her hair let down; with her shining countenance and her arms bared she looked even more beautiful than Homer’s goddesses of the ‘white arms’ and ‘fair ankles.’” The heroine, Callirhoe, is so beautiful people who encounter her think she’s Aphrodite—not like Aphrodite, actually Aphrodite. But unlike a major character in a Greek tragedy or Homeric epic, her story isn’t driven by fate and divine intervention; it’s violent, sordid, funny, surreal, and thoroughly human, sort of like Pirates of the Caribbean written by the Coen Brothers.

Without summarizing the whole plot (that would ruin the suspense, and it’s a story that depends on suspense): Callirhoe, noble daughter of a famous general, is married to a handsome but gullible young man, Chaereas, who suspects her of infidelity, flies into a jealous rage and kicks her so hard he kills her. Or at least it appears he’s killed her—actually she’s buried alive. When she wakes up in her tomb, it’s being pillaged by pirates, who take her prisoner, intending to sell her as a slave in Asia Minor (now Turkey). Through a series of plot twists, Callirhoe winds up married to another nobleman, Dionysius, having given birth in the meantime to Chaereas’s child—when Chaereas reappears on the scene with a search party from Syracuse.

If any of this rings a bell, it’s probably because Chaereas and Callirhoe resembles the romantic tales in Boccaccio’s Decameron, which provided much of the source material for Shakespeare. Chaereas and Callirhoe would have made a great play on the Elizabethan stage. But it’s very much a novel, dense with everyday detail and with the rich inner lives of its star-crossed lovers. You live in it, the way you do with any novel. It has an audience of one.

What’s most amazing about this novel is that it survives at all. Chaereas and Callirhoe is thought to have been quite popular in the Greek-speaking communities around the eastern Mediterranean, but like many prose works of the ancient world, it was very nearly lost in the Middle Ages. (Even Petronius’s Satyricon, one of the earliest novels written in Latin, barely survived, with major parts missing.) The complete Greek text only exists in one manuscript that dates to the 13th century. I first learned about it in Anne Carson’s Eros the Bittersweet; as a classicist, Carson takes it for granted that Chariton and his contemporaries (Heliodorus and Xenophon, among others) were the first novelists, even if their work lay forgotten for centuries.

Carson also has something particularly interesting to say about how we should approach romances and comic novels, where we know there will be a happy ending:

To create pleasure and pain at once is the novelist’s aim. We should dwell on this point for a moment. As readers, we are…drawn into a conflicted emotional response which approximates that of the lover’s soul divided by desire. Readership itself affords the aesthetic distance and obliquity necessary for this response. The reader’s emotions begin from a privileged position…We know the story will end happily. So we stand at an angle to the text…two levels of narrative reality float one upon another, without converging.

This is what makes always makes novels distinctive: they have readers. Not listeners or viewers. They’re not visual entertainment, and they’re not accompanied by music, as lyric poetry and epics always were in the Greek world. They’re read silently, one person at a time. The reader has to choose to keep reading the second, third, and fourth time they pick up the text; they have to be actively engaged. That’s what’s so haunting about a novel like this, written before printing, bookstores, or Kindles. It had to teach the reader how to appreciate it. Which is (in a different sense) still the challenge for novels today.

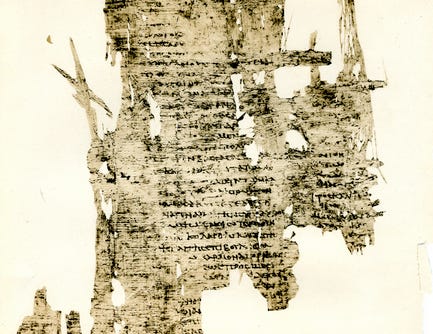

Image credit: Wikimedia Commons, an image of a 2nd century CE manuscript fragment of Chaereas and Callirhoe. The Egypt Exploration Society - Grenfell, B.P. et al. Fayûm towns and their papyri (London: The Egypt Exploration Society, 1900)