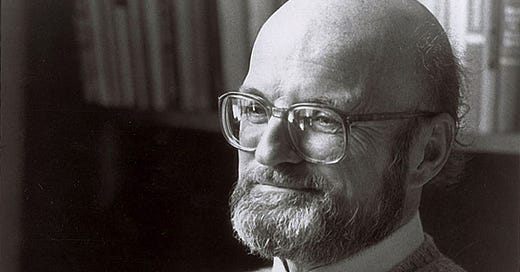

I read John Barth’s short story “Lost in the Funhouse” for the first time in graduate school, in my mid-twenties, out of mild curiosity. Although I was from Baltimore and he was the most famous of all Baltimore writers—it’s a pretty small group—I’d never had much interest in him before that; I thought of him as a writer of sprawling postmodern epics of the 1960s and 1970s who was hopelessly outdated and probably unreadable. None of my teachers had any interest in him. It was a dismissive time and I was an arrogant, dismissive twerp.

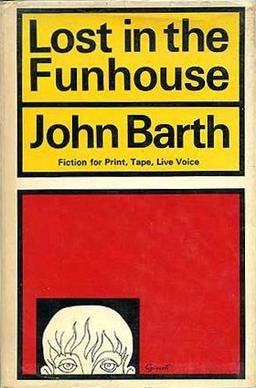

But then, as a grad student, I got interested in narrative theory and theories of the novel, and because I couldn’t find any courses to take, I started assembling my own floating syllabus. My teacher Charles Baxter, who had known Barth as a professor when he was a PhD student at SUNY-Buffalo in the early seventies, told me I had to read Barth’s essays “The Literature of Exhaustion” and “The Literature of Replenishment.” So I bought Barth’s first book of essays, The Friday Book, named because he devoted every Friday to writing nonfiction (judging from his output, he must have spent every other day writing fiction, including Saturdays and Sundays). And then at the Ann Arbor Library Book Sale, where you could buy a grocery bag full of books for $5, I happened upon a paperback of Lost in the Funhouse, and thought, what the hell, at least they’re short.

As it turns out, “Lost in the Funhouse” (the title story in the book) is one of my all-time favorite short stories, and the first piece of metafiction that ever made sense to me. It was written in 1968-69, around the same time as “The Literature of Exhaustion,” and although Barth was temperamentally conservative and not a fan of the student revolts of that time, he later acknowledged that his writings in those years had “a whiff of tear gas about them.” (I now think of Lost in the Funhouse as part of a little group of essential, groundbreaking experimental collections published in the late sixties, including J.G. Ballard’s The Atrocity Exhibition and Julio Cortázar’s End of the Game, better known by its later title, Blow-Up.) It’s an ars poetica story, a “why-I-write” statement of purpose, at once deeply nostalgic about the innocent pleasures of storytelling and utterly disillusioned about the possibility of recapturing that innocence.

It had its intended effect on me, although I was reading it more than thirty years later: it summed up the uneasiness I felt about the American realist tradition I was being trained to emulate (and, later, teach) as an MFA student. But it also worked on me the way any piece of fiction is supposed to work: it made me lose myself in full attention to what the writer is doing. Metafiction (I thought) was supposed to be cerebral and clever and stand at a distance from the reader, but this worked in exactly the opposite way. I felt completely, weirdly seen.

The basics: Ambrose is a 14-year-old who lives in rural Maryland (as Barth did) during World War II; he’s on a day trip to Ocean City, which is—then as now—a tacky beachside resort with a boardwalk and amusement park. (I visited there as a teenager Ambrose’s age in the 1980s). Ambrose spends much of the story gazing longingly at Magda, a 15-year-old family friend who came along for the ride. At the end of the day, he convinces Magda and his older brother Peter to go into the funhouse, where he promptly gets lost.

Metaphysically lost. One of my students recently described the funhouse as a “metaphor for everything,” which is true, until it becomes clear that this is a portrait of the artist as a young man:

He wonders: will he become a regular person? Something has gone wrong; his vaccination didn’t take; at the Boy-Scout initiation campfire he only pretended to be deeply moved, as he pretends to this hour that it is not so bad after all in the funhouse, and that he has a little limp. How long will it last? He envisions a truly astonishing funhouse, incredibly complex yet utterly controlled from a great central switchboard like the console of a pipe organ. Nobody had enough imagination. He could design such a place himself, wiring and all, and he’s only thirteen years old. He would be its operator: panel lights would show what was up in every cranny of its cunning of its multifarious vastness; a switch-flick would ease this fellow’s way, complicate that’s, to balance things out; if anyone seemed lost or frightened, all the operator had to do was.

He wishes he had never entered the funhouse. But he has. Then he wishes he were dead. But he’s not. Therefore he will construct funhouses for others and be their secret operator—though he would rather be among the lovers for whom funhouses are designed.

Sigh. More writing about writers! On the other hand, every novel is the story of how it was written, covertly or overtly. The best novels invent a new language and then teach you how to read it. (Many critics have said that in one form or another, but I’m paraphrasing John Updike, of all people, in a 1990s review of The God of Small Things that has always stuck in my mind.) I read this in my mid-to-late twenties with a shock of recognition like none I’ve ever experienced, before or since. I suspect David Foster Wallace felt the same way, and that’s what drove him to write “Westward the Course of Empire Takes its Way,” a novella-length sendup of Barth and “Lost in the Funhouse” that appeared in Girl With Curious Hair. I always teach the two together, as a way of showing my students what happens when you love a work of art so much it drives you over the edge. My own summation of “Lost in the Funhouse” appeared in my story “The Ax,” originally published in Tin House in 2014 (it’ll appear in revised form in Storyknife):

The thing about being a writer of fiction is this: you spend a lot of time having feelings which are not really your feelings to have. Or conjuring feelings in others that aren’t your feelings to give. The risk is that you lose touch with any sense of reality and just float around in a fog. You can almost imagine handing the reader an ax and saying, here, solve this problem for me. Prove to me I’m real. Free me from this mildness.

Almost.

Barth died last week in Bonita Springs, Florida, at 93, having been absent from the literary scene for decades. I’m sad I never got to meet him in person. But I met him on the page, which for fiction writers—for better or worse—is the important thing. Or is it? In the end, which mattered to him more?

The point of having all these mirrors, I think he might have said, is not having to choose which reflection matters. You can love them all.